June 2003 35

■ Dave Linstrum

To launch the Hawk, release propeller tip first,

then let the model fly gently from your hand.

Do not throw!

DEDICATED SCALE enthusiasts often go to great lengths to find obscure full-scale

aircraft to model. They delight in finding something that few fliers have ever heard of,

much less modeled. They spend hours in libraries or on the Internet looking for that

obscure subject that will be the envy of their peers.

I found a complete illustrated dossier on the Cooper-Travers Hawk by accident. I

was in Los Angeles, California (I live in Orlando, Florida), visiting my daughter who

lives in Beverly Hills. I was driving along an urban street and came upon a roadside

newsstand that appeared to have a broad selection of periodicals. I immediately

spotted the July 2001 Aeroplane Monthly—a venerable British publication that

usually has the latest news on aircraft and often has detailed historical articles.

This issue had a gem: a fully illustrated (photos and detailed three-view)

presentation of the 1924 Cooper-Travers Hawk. When I saw the query note by Editor

Michael Oakey, I was hooked! He stated: “It represents a challenging subject for the

aeromodellers among our readership—who will be the first to produce a flying scale

model?”

Thus challenged, I sketched out the model you see here on an SWA barf bag at

35,000 feet shortly after leaving the Los Angeles International Airport. When I got

home, I sent Editor Oakey (himself an aeromodeler) my terse E-mail reply—even

before I glued the first sticks of my FAC (Flying Aces Club) Profile No-Cal Scale

design. I wrote: “A Yank will be first!” He sent his E-mail reply

from London that he was looking forward to hearing more.

I built the model, took flight photos, and mailed them to him as

proof. Indeed, I was first.

In the article “Lesser-Known Aircraft” by distinguished aerohistorian

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume, there is a photo of casual,

intrepid test pilot James L. Travers taken when he was a regular

flier at Hendon Aerodrome (London) in 1912. There is also a

photo of Lt. Col. Jim Travers on approach at Croydon Aerodrome

(London) taken the afternoon of February 14, 1924, captioned:

“ … The aircraft and its designer are seconds from disaster.

The picture shows clearly the extremely deep undercambered

Gottingen wing section, as well as revealing the five-degree angle

of incidence on the unbraced tailplane.”

My ink sketch from that photo shows these two fatal design

flaws. The thick wing was to accommodate two passengers in the

wing root—one on either side of the pilot’s cockpit. Cooper put

the positive incidence in the tailplane, and it gave Travers pause

before he took off, but not enough pause …

A fatal crash on the first test flight was proof enough for me to

eliminate both of those flaws from my model design. I used a

simple undercambered wing rib and set the stabilizer at 0°—a

setup proven on my past No-Cal designs (such as the Dornier

Falke) as stable for Free Flight. I was proven right—and no test

pilot was put at risk.

As Aeroplane stated, “The short life of the one-off Cooper-

Travers Hawk of 1924 has denied it a place in aviation history.

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume investigates why this revolutionary

design ended in a flaming pyre.”

You do not need further history to build this simple replica, but

you can order a back issue of the 7/01 Aeroplane if you want more

details or want to design your own Radio Control version. See the

end of this article for details. I thank that publication and Editor

Oakey for his kind permission to reproduce here the beautifully

drawn Giuseppe Picarella three-view and the preceding quotes.

Giuseppe is a maestro.

CONSTRUCTION

Preparation: Make photocopies (two each—the second set is for

patterns) of the two letter-size plates of building plans. This way

36 MODEL AVIATION

you can avoid cutting up your Model

Aviation. Be sure to hold the magazine

down tight on the copier glass to capture

the image near the binding.

Tape the building plates together along

match line A-B with 3M Scotch Magic

Tape. Tape the plates to your building

board (an 11 x 17-inch scrap of pinstickable

Fome-Cor will do), and cover

with waxed paper to prevent glued balsa

from adhering to the plans.

Materials and Tools: Free Flight stickand-

tissue construction and flying require

special tools and materials. At the least,

you must have an X-Acto (or similar)

model knife with a #11 pointed blade,

bead-head dressmaker pins, a self-healing

cutting board (or a scrap of dark artist’s

matboard), glue (use Duco cement or thickgel

CyA [cyanoacrylate]), a glue stick for

covering with tissue, and needle-nose pliers

for bending the rear hook and propeller

shaft.

Get the preceding items at your local

Wal-Mart. You may need to go to an art

store for the cutting/matboard. Cutting balsa on this is a pleasure.

Do not cut on the plans!

Type: FF FAC Profile No-Cal Scale

Wingspan: 16 inches

Power: 11- to 12-inch loop FAI Tan

II Rubber

Flying weight: 8-10 grams

Construction: Balsa sheet and strip

Covering/finish: Yellow or beige

tissue, Krylon Espresso aerosol

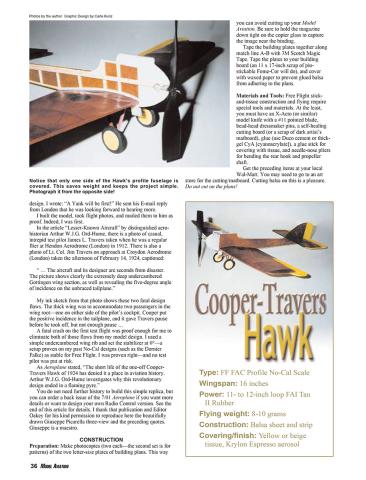

Notice that only one side of the Hawk’s profile fuselage is

covered. This saves weight and keeps the project simple.

Photograph it from the opposite side!

Photos by the author Graphic Design by Carla Kunz

June 2003 37

Few parts make for rapid building, even with the curved tips. All of the parts are shown,

pinned down for drying on the plans. This is a fun project.

Use artist’s matboard or 1⁄16 balsa for templates to form the fin, wingtips, and stabilizer.

Form these parts from wetted 1⁄32 strips.

Most hobby shops do not have the

light balsa and tissue needed to build this

model. An excellent mail-order source is

Peck-Polymers (see the company’s ad in

Model Aviation). To order the complete

catalog for $4, which is a good

investment, call (619) 448-1818. Mail

order is a great resource. Peck is the best

for Free Flight.

You should order 1⁄16 and 1⁄32 balsa

(get small sheets and a dozen 1⁄16 square

sticks), 1⁄32 plywood, a sheet of yellow or

tan Esaki tissue, a 4-inch black square-tip

plastic propeller, a pack of 1⁄32-inchdiameter

shafts, a pack of white nylon

Peanut bearings, a pack of 1-inch black

plastic wheels (unless you want to cut

your own from white carryout tray foam),

a pack of 1⁄8-inch FAI Tan II rubber, a

Peck 5:1 winder for rubber, and the XActo.

Good books to have are Don Ross’s

Rubber Power Flying Models and

Building the Peck ROG by Bill Warner.

Both have many photos and excellent

drawings by Jim Kaman. They will be

treasured in your modeling library. Both

are available from Peck-Polymers.

If you have no stick-and-tissue

experience, order some simple kits: an

AMA Cub (Delta Dart), a Peck ROG, and

perhaps a Sky Bunny. These have

complete, illustrated instructions that will

make you skillful in a hurry. The Hawk is

not a beginner’s model!

Building: I will not tell you how to glue

Part A to Part B; the aforementioned kits

and books will teach you that. The simple

Cooper-Travers Hawk is not an ARF

(Almost Ready-to Fly) with an instruction

book; it is a craftsman’s project requiring

some basic skills.

The sliced wing ribs may be new to

you. Make a rib-slicing pattern from 1⁄32

plywood using the extra plans copy (gluestick

the pattern to the plywood). Cut a

sheet of 1⁄16 balsa to the length of the

center rib, then tape it to the cutting board

at the bottom of the balsa. Slice away

with the X-Acto knife at the top and

discard the scrap, then move the pattern

down 1⁄16 inch. Carefully slice again; you

may need a couple of light strokes.

Cut a full set of ribs. Taper them from

the rear before you glue them in place to

the leading edge and trailing edge. Note

that there is only one center rib, which is

added as you put in the 1-inch dihedral.

Be sure that half of the wing is pinned

down flat as you raise the other tip.

Another unusual method is the wet

lamination of balsa for the round-corner

tips, aileron ends, and fin/rudder. This

requires making forms from artists’

matboard or 1⁄16 balsa; see the photo.

Using the extra “patterns” photocopy

of the plans, glue-stick the tips (one on

each wing and stabilizer) and fin/rudder

to the pattern material. Cut to the inside

line of the double lines of the curved part.

Allow some extra (straight) beyond the

end of the curve; this is for taping the

lamination to the form.

The lamination will be two strips of 1⁄32 x

1⁄16 that appear 1⁄16-inch wide on the plans to

match the 1⁄16 square sticks. Lightly sand the

edges of the patterns and wax them to

prevent glue from sticking the part to the

form.

Cut the strips to length a bit longer than

the form edge, and soak them in hot water

in a saucer. Two at a time, blot excess water

with a paper napkin. Apply a bead of

Titebond or Elmer’s carpenter’s glue to one

strip, then stack the other on top of it,

wiping away any glue that leaks out the

edge. Your lamination is ready to bend

around the form.

Cut two small pieces of 3M Scotch

Magic Tape to hold down the ends. Affix

one end of the strips to the form, pull firmly

and tight to form around the curve, then

affix the other end. Now you are ready for

the fun part.

Put a coffee mug upside down in the

microwave and set the wet part/form atop it.

Microwave for one minute on high, and

presto! You have a permanently curved part

that only needs cutting loose from the form

at the ends. Cut to the line you see at the

end of “straight” for exact length. Discard

the excess with tape. Repeat until you have

all parts; the stabilizer and wingtip/aileron

forms get used twice.

This is the easy way to make curves on a

Finished parts ready for assembly. Black propeller is smallest North Pacific/Peck size.

You can clearly see the undercambered rib strips. The wheels are made from 1⁄16 sheet

foam with silver paper hubs.

38 MODEL AVIATION

stick-and-tissue model—and it’s much

easier than cutting segments of curves from

1⁄16 balsa sheet and piecing them together.

This is how they did it in the 1930s, but

they did not have such water-based glues or

microwaves then. Technology can make

building faster and better.

Assembly and Painting: After parts are

covered with tissue (use the glue stick on

balsa, then pat the tissue down and trim),

mask off the ailerons, rudder, and elevator

with low-tack masking tape and paper. If

you do not want an accurate color, simply

use the colored tissue. Note that the flying

surfaces are covered on the top only and the

body/fin left side only.

Get a can of Krylon Short Cuts acrylic

aerosol in Espresso (color SCS-035). It will

give your tissue a coffeelike tone—similar

to aged shellac on 1924 aircraft fabric.

Carefully mist a light coat on the exposed

tissue and let it dry before unmasking. Paint

the nose with aluminum acrylic paint from

Wal-Mart.

Attach the rear hook and bearing to the

motorstick (see details on plans), then glue

to the right side of the body as shown on

the plans. Attach the stabilizer, then attach

the fin to the body. Tilt the right side of

the stabilizer up slightly, as seen from the

rear; this will induce a natural right-turn

circle.

Attach the wing to the top of the body;

you may want to pin it at the leading edge

and trailing edge while the Duco dries.

Check to make sure that it is level.

Attach the splayed 1⁄32 plywood landinggear

struts and add the wheels, which can

be glued on. Rotating wheels are not

required; this model is hand launched only.

Add the 1⁄32 plywood rear skid.

Make a rubber motor in approximately a

12-inch loop, tying the ends in a square

knot. Lubricate the motor with Johnson’s

Baby Shampoo and wipe off the excess.

Hang the motor from the shaft and the

rear hook, then wind in a few hand turns,

rotating the propeller clockwise while

holding the nose. Let the propeller breeze

blow in your face—it’s cool!

Check the balance (see plans) with the

motor installed. If necessary, add clay to

the nose in the sheeted section. Correct

balance is essential for Free Flight—or for

any aircraft, piloted or not.

Go to a copy shop and ask for a

discarded box used to ship letter-size copy

paper. Do not use grocery-store boxes; the

lids implode. Put your model in your

storage/transport box, but don’t put any

heavy objects in there with it—a rolling

winder could damage the model.

Flying: It is pointless to test-glide such a

small model. If you fly outdoors (it is

okay to fly in a school gym if it is windy

outdoors), hand wind roughly 200 turns

into the motor and launch the model

straight and level into the wind (10 mph

or less). Do not throw the model!

Your Hawk should fly in a loose right

circle, climbing slightly. Adjust it by

bending the nose bearing to the right for

right thrust and bending the right aileron

down by cracking the tip ribs slightly and

gluing them. This will keep the wing up

(like an aileron) in a turn.

Progress to stretch-winding with the

Peck winder. You will need a flying

buddy to hold the model (upside-down)

by the nose bearing/propeller hub while

you attach the winder and stretch the

motor out approximately twice its length

to the rear.

Put in roughly 100 winder turns while

coming in, then remove the motor from

the winder and attach it to the rear hook.

Take the model from your buddy (give

him/her the winder), and gently launch it.

It should climb out in a loose right circle.

I hope you enjoyed the aviation history

and building this replica of an ill-fated

aircraft. Good luck with your Cooper-

Travers Hawk. Happy landings!

For an issue of the 7/01 Aeroplane

Monthly, send an airmail letter to the

Circulation Department, Aeroplane

Monthly, King’s Reach Tower, Stamford

St., London SE19LS, England.

The cover price is 3.20 pounds, but the

back-issue price plus postage would be in

euros. The easiest way to pay is by major

credit card so there is no trouble with

exchange rates. Include your name as it is

printed on the card, the card’s expiration

date, and the name of the card. That will

expedite your order.

You may order a copy by inquiring by

E-mail to [email protected] or

[email protected]. MA

Dave Linstrum

4016 Maguire Blvd. Apt. 3314

Orlando FL 32803

June 2003 39

Test pilot Lt. Col. Jim Travers flies Cooper-Travers Hawk on approach at Croydon (original London airport) on February 14,

1924, just seconds before fatal crash on first flight. Extremely deep undercambered Gottingen airfoil and 5° positive

incidence on tailplane were likely causes for crash. Ink sketch by author is from photo by Cecil Arthur Rae, who was later a

test pilot for British aircraft manufacturer Boulton Paul.

Edition: Model Aviation - 2003/06

Page Numbers: 35,36,37,38,39,40,41

Edition: Model Aviation - 2003/06

Page Numbers: 35,36,37,38,39,40,41

June 2003 35

■ Dave Linstrum

To launch the Hawk, release propeller tip first,

then let the model fly gently from your hand.

Do not throw!

DEDICATED SCALE enthusiasts often go to great lengths to find obscure full-scale

aircraft to model. They delight in finding something that few fliers have ever heard of,

much less modeled. They spend hours in libraries or on the Internet looking for that

obscure subject that will be the envy of their peers.

I found a complete illustrated dossier on the Cooper-Travers Hawk by accident. I

was in Los Angeles, California (I live in Orlando, Florida), visiting my daughter who

lives in Beverly Hills. I was driving along an urban street and came upon a roadside

newsstand that appeared to have a broad selection of periodicals. I immediately

spotted the July 2001 Aeroplane Monthly—a venerable British publication that

usually has the latest news on aircraft and often has detailed historical articles.

This issue had a gem: a fully illustrated (photos and detailed three-view)

presentation of the 1924 Cooper-Travers Hawk. When I saw the query note by Editor

Michael Oakey, I was hooked! He stated: “It represents a challenging subject for the

aeromodellers among our readership—who will be the first to produce a flying scale

model?”

Thus challenged, I sketched out the model you see here on an SWA barf bag at

35,000 feet shortly after leaving the Los Angeles International Airport. When I got

home, I sent Editor Oakey (himself an aeromodeler) my terse E-mail reply—even

before I glued the first sticks of my FAC (Flying Aces Club) Profile No-Cal Scale

design. I wrote: “A Yank will be first!” He sent his E-mail reply

from London that he was looking forward to hearing more.

I built the model, took flight photos, and mailed them to him as

proof. Indeed, I was first.

In the article “Lesser-Known Aircraft” by distinguished aerohistorian

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume, there is a photo of casual,

intrepid test pilot James L. Travers taken when he was a regular

flier at Hendon Aerodrome (London) in 1912. There is also a

photo of Lt. Col. Jim Travers on approach at Croydon Aerodrome

(London) taken the afternoon of February 14, 1924, captioned:

“ … The aircraft and its designer are seconds from disaster.

The picture shows clearly the extremely deep undercambered

Gottingen wing section, as well as revealing the five-degree angle

of incidence on the unbraced tailplane.”

My ink sketch from that photo shows these two fatal design

flaws. The thick wing was to accommodate two passengers in the

wing root—one on either side of the pilot’s cockpit. Cooper put

the positive incidence in the tailplane, and it gave Travers pause

before he took off, but not enough pause …

A fatal crash on the first test flight was proof enough for me to

eliminate both of those flaws from my model design. I used a

simple undercambered wing rib and set the stabilizer at 0°—a

setup proven on my past No-Cal designs (such as the Dornier

Falke) as stable for Free Flight. I was proven right—and no test

pilot was put at risk.

As Aeroplane stated, “The short life of the one-off Cooper-

Travers Hawk of 1924 has denied it a place in aviation history.

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume investigates why this revolutionary

design ended in a flaming pyre.”

You do not need further history to build this simple replica, but

you can order a back issue of the 7/01 Aeroplane if you want more

details or want to design your own Radio Control version. See the

end of this article for details. I thank that publication and Editor

Oakey for his kind permission to reproduce here the beautifully

drawn Giuseppe Picarella three-view and the preceding quotes.

Giuseppe is a maestro.

CONSTRUCTION

Preparation: Make photocopies (two each—the second set is for

patterns) of the two letter-size plates of building plans. This way

36 MODEL AVIATION

you can avoid cutting up your Model

Aviation. Be sure to hold the magazine

down tight on the copier glass to capture

the image near the binding.

Tape the building plates together along

match line A-B with 3M Scotch Magic

Tape. Tape the plates to your building

board (an 11 x 17-inch scrap of pinstickable

Fome-Cor will do), and cover

with waxed paper to prevent glued balsa

from adhering to the plans.

Materials and Tools: Free Flight stickand-

tissue construction and flying require

special tools and materials. At the least,

you must have an X-Acto (or similar)

model knife with a #11 pointed blade,

bead-head dressmaker pins, a self-healing

cutting board (or a scrap of dark artist’s

matboard), glue (use Duco cement or thickgel

CyA [cyanoacrylate]), a glue stick for

covering with tissue, and needle-nose pliers

for bending the rear hook and propeller

shaft.

Get the preceding items at your local

Wal-Mart. You may need to go to an art

store for the cutting/matboard. Cutting balsa on this is a pleasure.

Do not cut on the plans!

Type: FF FAC Profile No-Cal Scale

Wingspan: 16 inches

Power: 11- to 12-inch loop FAI Tan

II Rubber

Flying weight: 8-10 grams

Construction: Balsa sheet and strip

Covering/finish: Yellow or beige

tissue, Krylon Espresso aerosol

Notice that only one side of the Hawk’s profile fuselage is

covered. This saves weight and keeps the project simple.

Photograph it from the opposite side!

Photos by the author Graphic Design by Carla Kunz

June 2003 37

Few parts make for rapid building, even with the curved tips. All of the parts are shown,

pinned down for drying on the plans. This is a fun project.

Use artist’s matboard or 1⁄16 balsa for templates to form the fin, wingtips, and stabilizer.

Form these parts from wetted 1⁄32 strips.

Most hobby shops do not have the

light balsa and tissue needed to build this

model. An excellent mail-order source is

Peck-Polymers (see the company’s ad in

Model Aviation). To order the complete

catalog for $4, which is a good

investment, call (619) 448-1818. Mail

order is a great resource. Peck is the best

for Free Flight.

You should order 1⁄16 and 1⁄32 balsa

(get small sheets and a dozen 1⁄16 square

sticks), 1⁄32 plywood, a sheet of yellow or

tan Esaki tissue, a 4-inch black square-tip

plastic propeller, a pack of 1⁄32-inchdiameter

shafts, a pack of white nylon

Peanut bearings, a pack of 1-inch black

plastic wheels (unless you want to cut

your own from white carryout tray foam),

a pack of 1⁄8-inch FAI Tan II rubber, a

Peck 5:1 winder for rubber, and the XActo.

Good books to have are Don Ross’s

Rubber Power Flying Models and

Building the Peck ROG by Bill Warner.

Both have many photos and excellent

drawings by Jim Kaman. They will be

treasured in your modeling library. Both

are available from Peck-Polymers.

If you have no stick-and-tissue

experience, order some simple kits: an

AMA Cub (Delta Dart), a Peck ROG, and

perhaps a Sky Bunny. These have

complete, illustrated instructions that will

make you skillful in a hurry. The Hawk is

not a beginner’s model!

Building: I will not tell you how to glue

Part A to Part B; the aforementioned kits

and books will teach you that. The simple

Cooper-Travers Hawk is not an ARF

(Almost Ready-to Fly) with an instruction

book; it is a craftsman’s project requiring

some basic skills.

The sliced wing ribs may be new to

you. Make a rib-slicing pattern from 1⁄32

plywood using the extra plans copy (gluestick

the pattern to the plywood). Cut a

sheet of 1⁄16 balsa to the length of the

center rib, then tape it to the cutting board

at the bottom of the balsa. Slice away

with the X-Acto knife at the top and

discard the scrap, then move the pattern

down 1⁄16 inch. Carefully slice again; you

may need a couple of light strokes.

Cut a full set of ribs. Taper them from

the rear before you glue them in place to

the leading edge and trailing edge. Note

that there is only one center rib, which is

added as you put in the 1-inch dihedral.

Be sure that half of the wing is pinned

down flat as you raise the other tip.

Another unusual method is the wet

lamination of balsa for the round-corner

tips, aileron ends, and fin/rudder. This

requires making forms from artists’

matboard or 1⁄16 balsa; see the photo.

Using the extra “patterns” photocopy

of the plans, glue-stick the tips (one on

each wing and stabilizer) and fin/rudder

to the pattern material. Cut to the inside

line of the double lines of the curved part.

Allow some extra (straight) beyond the

end of the curve; this is for taping the

lamination to the form.

The lamination will be two strips of 1⁄32 x

1⁄16 that appear 1⁄16-inch wide on the plans to

match the 1⁄16 square sticks. Lightly sand the

edges of the patterns and wax them to

prevent glue from sticking the part to the

form.

Cut the strips to length a bit longer than

the form edge, and soak them in hot water

in a saucer. Two at a time, blot excess water

with a paper napkin. Apply a bead of

Titebond or Elmer’s carpenter’s glue to one

strip, then stack the other on top of it,

wiping away any glue that leaks out the

edge. Your lamination is ready to bend

around the form.

Cut two small pieces of 3M Scotch

Magic Tape to hold down the ends. Affix

one end of the strips to the form, pull firmly

and tight to form around the curve, then

affix the other end. Now you are ready for

the fun part.

Put a coffee mug upside down in the

microwave and set the wet part/form atop it.

Microwave for one minute on high, and

presto! You have a permanently curved part

that only needs cutting loose from the form

at the ends. Cut to the line you see at the

end of “straight” for exact length. Discard

the excess with tape. Repeat until you have

all parts; the stabilizer and wingtip/aileron

forms get used twice.

This is the easy way to make curves on a

Finished parts ready for assembly. Black propeller is smallest North Pacific/Peck size.

You can clearly see the undercambered rib strips. The wheels are made from 1⁄16 sheet

foam with silver paper hubs.

38 MODEL AVIATION

stick-and-tissue model—and it’s much

easier than cutting segments of curves from

1⁄16 balsa sheet and piecing them together.

This is how they did it in the 1930s, but

they did not have such water-based glues or

microwaves then. Technology can make

building faster and better.

Assembly and Painting: After parts are

covered with tissue (use the glue stick on

balsa, then pat the tissue down and trim),

mask off the ailerons, rudder, and elevator

with low-tack masking tape and paper. If

you do not want an accurate color, simply

use the colored tissue. Note that the flying

surfaces are covered on the top only and the

body/fin left side only.

Get a can of Krylon Short Cuts acrylic

aerosol in Espresso (color SCS-035). It will

give your tissue a coffeelike tone—similar

to aged shellac on 1924 aircraft fabric.

Carefully mist a light coat on the exposed

tissue and let it dry before unmasking. Paint

the nose with aluminum acrylic paint from

Wal-Mart.

Attach the rear hook and bearing to the

motorstick (see details on plans), then glue

to the right side of the body as shown on

the plans. Attach the stabilizer, then attach

the fin to the body. Tilt the right side of

the stabilizer up slightly, as seen from the

rear; this will induce a natural right-turn

circle.

Attach the wing to the top of the body;

you may want to pin it at the leading edge

and trailing edge while the Duco dries.

Check to make sure that it is level.

Attach the splayed 1⁄32 plywood landinggear

struts and add the wheels, which can

be glued on. Rotating wheels are not

required; this model is hand launched only.

Add the 1⁄32 plywood rear skid.

Make a rubber motor in approximately a

12-inch loop, tying the ends in a square

knot. Lubricate the motor with Johnson’s

Baby Shampoo and wipe off the excess.

Hang the motor from the shaft and the

rear hook, then wind in a few hand turns,

rotating the propeller clockwise while

holding the nose. Let the propeller breeze

blow in your face—it’s cool!

Check the balance (see plans) with the

motor installed. If necessary, add clay to

the nose in the sheeted section. Correct

balance is essential for Free Flight—or for

any aircraft, piloted or not.

Go to a copy shop and ask for a

discarded box used to ship letter-size copy

paper. Do not use grocery-store boxes; the

lids implode. Put your model in your

storage/transport box, but don’t put any

heavy objects in there with it—a rolling

winder could damage the model.

Flying: It is pointless to test-glide such a

small model. If you fly outdoors (it is

okay to fly in a school gym if it is windy

outdoors), hand wind roughly 200 turns

into the motor and launch the model

straight and level into the wind (10 mph

or less). Do not throw the model!

Your Hawk should fly in a loose right

circle, climbing slightly. Adjust it by

bending the nose bearing to the right for

right thrust and bending the right aileron

down by cracking the tip ribs slightly and

gluing them. This will keep the wing up

(like an aileron) in a turn.

Progress to stretch-winding with the

Peck winder. You will need a flying

buddy to hold the model (upside-down)

by the nose bearing/propeller hub while

you attach the winder and stretch the

motor out approximately twice its length

to the rear.

Put in roughly 100 winder turns while

coming in, then remove the motor from

the winder and attach it to the rear hook.

Take the model from your buddy (give

him/her the winder), and gently launch it.

It should climb out in a loose right circle.

I hope you enjoyed the aviation history

and building this replica of an ill-fated

aircraft. Good luck with your Cooper-

Travers Hawk. Happy landings!

For an issue of the 7/01 Aeroplane

Monthly, send an airmail letter to the

Circulation Department, Aeroplane

Monthly, King’s Reach Tower, Stamford

St., London SE19LS, England.

The cover price is 3.20 pounds, but the

back-issue price plus postage would be in

euros. The easiest way to pay is by major

credit card so there is no trouble with

exchange rates. Include your name as it is

printed on the card, the card’s expiration

date, and the name of the card. That will

expedite your order.

You may order a copy by inquiring by

E-mail to [email protected] or

[email protected]. MA

Dave Linstrum

4016 Maguire Blvd. Apt. 3314

Orlando FL 32803

June 2003 39

Test pilot Lt. Col. Jim Travers flies Cooper-Travers Hawk on approach at Croydon (original London airport) on February 14,

1924, just seconds before fatal crash on first flight. Extremely deep undercambered Gottingen airfoil and 5° positive

incidence on tailplane were likely causes for crash. Ink sketch by author is from photo by Cecil Arthur Rae, who was later a

test pilot for British aircraft manufacturer Boulton Paul.

Edition: Model Aviation - 2003/06

Page Numbers: 35,36,37,38,39,40,41

June 2003 35

■ Dave Linstrum

To launch the Hawk, release propeller tip first,

then let the model fly gently from your hand.

Do not throw!

DEDICATED SCALE enthusiasts often go to great lengths to find obscure full-scale

aircraft to model. They delight in finding something that few fliers have ever heard of,

much less modeled. They spend hours in libraries or on the Internet looking for that

obscure subject that will be the envy of their peers.

I found a complete illustrated dossier on the Cooper-Travers Hawk by accident. I

was in Los Angeles, California (I live in Orlando, Florida), visiting my daughter who

lives in Beverly Hills. I was driving along an urban street and came upon a roadside

newsstand that appeared to have a broad selection of periodicals. I immediately

spotted the July 2001 Aeroplane Monthly—a venerable British publication that

usually has the latest news on aircraft and often has detailed historical articles.

This issue had a gem: a fully illustrated (photos and detailed three-view)

presentation of the 1924 Cooper-Travers Hawk. When I saw the query note by Editor

Michael Oakey, I was hooked! He stated: “It represents a challenging subject for the

aeromodellers among our readership—who will be the first to produce a flying scale

model?”

Thus challenged, I sketched out the model you see here on an SWA barf bag at

35,000 feet shortly after leaving the Los Angeles International Airport. When I got

home, I sent Editor Oakey (himself an aeromodeler) my terse E-mail reply—even

before I glued the first sticks of my FAC (Flying Aces Club) Profile No-Cal Scale

design. I wrote: “A Yank will be first!” He sent his E-mail reply

from London that he was looking forward to hearing more.

I built the model, took flight photos, and mailed them to him as

proof. Indeed, I was first.

In the article “Lesser-Known Aircraft” by distinguished aerohistorian

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume, there is a photo of casual,

intrepid test pilot James L. Travers taken when he was a regular

flier at Hendon Aerodrome (London) in 1912. There is also a

photo of Lt. Col. Jim Travers on approach at Croydon Aerodrome

(London) taken the afternoon of February 14, 1924, captioned:

“ … The aircraft and its designer are seconds from disaster.

The picture shows clearly the extremely deep undercambered

Gottingen wing section, as well as revealing the five-degree angle

of incidence on the unbraced tailplane.”

My ink sketch from that photo shows these two fatal design

flaws. The thick wing was to accommodate two passengers in the

wing root—one on either side of the pilot’s cockpit. Cooper put

the positive incidence in the tailplane, and it gave Travers pause

before he took off, but not enough pause …

A fatal crash on the first test flight was proof enough for me to

eliminate both of those flaws from my model design. I used a

simple undercambered wing rib and set the stabilizer at 0°—a

setup proven on my past No-Cal designs (such as the Dornier

Falke) as stable for Free Flight. I was proven right—and no test

pilot was put at risk.

As Aeroplane stated, “The short life of the one-off Cooper-

Travers Hawk of 1924 has denied it a place in aviation history.

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume investigates why this revolutionary

design ended in a flaming pyre.”

You do not need further history to build this simple replica, but

you can order a back issue of the 7/01 Aeroplane if you want more

details or want to design your own Radio Control version. See the

end of this article for details. I thank that publication and Editor

Oakey for his kind permission to reproduce here the beautifully

drawn Giuseppe Picarella three-view and the preceding quotes.

Giuseppe is a maestro.

CONSTRUCTION

Preparation: Make photocopies (two each—the second set is for

patterns) of the two letter-size plates of building plans. This way

36 MODEL AVIATION

you can avoid cutting up your Model

Aviation. Be sure to hold the magazine

down tight on the copier glass to capture

the image near the binding.

Tape the building plates together along

match line A-B with 3M Scotch Magic

Tape. Tape the plates to your building

board (an 11 x 17-inch scrap of pinstickable

Fome-Cor will do), and cover

with waxed paper to prevent glued balsa

from adhering to the plans.

Materials and Tools: Free Flight stickand-

tissue construction and flying require

special tools and materials. At the least,

you must have an X-Acto (or similar)

model knife with a #11 pointed blade,

bead-head dressmaker pins, a self-healing

cutting board (or a scrap of dark artist’s

matboard), glue (use Duco cement or thickgel

CyA [cyanoacrylate]), a glue stick for

covering with tissue, and needle-nose pliers

for bending the rear hook and propeller

shaft.

Get the preceding items at your local

Wal-Mart. You may need to go to an art

store for the cutting/matboard. Cutting balsa on this is a pleasure.

Do not cut on the plans!

Type: FF FAC Profile No-Cal Scale

Wingspan: 16 inches

Power: 11- to 12-inch loop FAI Tan

II Rubber

Flying weight: 8-10 grams

Construction: Balsa sheet and strip

Covering/finish: Yellow or beige

tissue, Krylon Espresso aerosol

Notice that only one side of the Hawk’s profile fuselage is

covered. This saves weight and keeps the project simple.

Photograph it from the opposite side!

Photos by the author Graphic Design by Carla Kunz

June 2003 37

Few parts make for rapid building, even with the curved tips. All of the parts are shown,

pinned down for drying on the plans. This is a fun project.

Use artist’s matboard or 1⁄16 balsa for templates to form the fin, wingtips, and stabilizer.

Form these parts from wetted 1⁄32 strips.

Most hobby shops do not have the

light balsa and tissue needed to build this

model. An excellent mail-order source is

Peck-Polymers (see the company’s ad in

Model Aviation). To order the complete

catalog for $4, which is a good

investment, call (619) 448-1818. Mail

order is a great resource. Peck is the best

for Free Flight.

You should order 1⁄16 and 1⁄32 balsa

(get small sheets and a dozen 1⁄16 square

sticks), 1⁄32 plywood, a sheet of yellow or

tan Esaki tissue, a 4-inch black square-tip

plastic propeller, a pack of 1⁄32-inchdiameter

shafts, a pack of white nylon

Peanut bearings, a pack of 1-inch black

plastic wheels (unless you want to cut

your own from white carryout tray foam),

a pack of 1⁄8-inch FAI Tan II rubber, a

Peck 5:1 winder for rubber, and the XActo.

Good books to have are Don Ross’s

Rubber Power Flying Models and

Building the Peck ROG by Bill Warner.

Both have many photos and excellent

drawings by Jim Kaman. They will be

treasured in your modeling library. Both

are available from Peck-Polymers.

If you have no stick-and-tissue

experience, order some simple kits: an

AMA Cub (Delta Dart), a Peck ROG, and

perhaps a Sky Bunny. These have

complete, illustrated instructions that will

make you skillful in a hurry. The Hawk is

not a beginner’s model!

Building: I will not tell you how to glue

Part A to Part B; the aforementioned kits

and books will teach you that. The simple

Cooper-Travers Hawk is not an ARF

(Almost Ready-to Fly) with an instruction

book; it is a craftsman’s project requiring

some basic skills.

The sliced wing ribs may be new to

you. Make a rib-slicing pattern from 1⁄32

plywood using the extra plans copy (gluestick

the pattern to the plywood). Cut a

sheet of 1⁄16 balsa to the length of the

center rib, then tape it to the cutting board

at the bottom of the balsa. Slice away

with the X-Acto knife at the top and

discard the scrap, then move the pattern

down 1⁄16 inch. Carefully slice again; you

may need a couple of light strokes.

Cut a full set of ribs. Taper them from

the rear before you glue them in place to

the leading edge and trailing edge. Note

that there is only one center rib, which is

added as you put in the 1-inch dihedral.

Be sure that half of the wing is pinned

down flat as you raise the other tip.

Another unusual method is the wet

lamination of balsa for the round-corner

tips, aileron ends, and fin/rudder. This

requires making forms from artists’

matboard or 1⁄16 balsa; see the photo.

Using the extra “patterns” photocopy

of the plans, glue-stick the tips (one on

each wing and stabilizer) and fin/rudder

to the pattern material. Cut to the inside

line of the double lines of the curved part.

Allow some extra (straight) beyond the

end of the curve; this is for taping the

lamination to the form.

The lamination will be two strips of 1⁄32 x

1⁄16 that appear 1⁄16-inch wide on the plans to

match the 1⁄16 square sticks. Lightly sand the

edges of the patterns and wax them to

prevent glue from sticking the part to the

form.

Cut the strips to length a bit longer than

the form edge, and soak them in hot water

in a saucer. Two at a time, blot excess water

with a paper napkin. Apply a bead of

Titebond or Elmer’s carpenter’s glue to one

strip, then stack the other on top of it,

wiping away any glue that leaks out the

edge. Your lamination is ready to bend

around the form.

Cut two small pieces of 3M Scotch

Magic Tape to hold down the ends. Affix

one end of the strips to the form, pull firmly

and tight to form around the curve, then

affix the other end. Now you are ready for

the fun part.

Put a coffee mug upside down in the

microwave and set the wet part/form atop it.

Microwave for one minute on high, and

presto! You have a permanently curved part

that only needs cutting loose from the form

at the ends. Cut to the line you see at the

end of “straight” for exact length. Discard

the excess with tape. Repeat until you have

all parts; the stabilizer and wingtip/aileron

forms get used twice.

This is the easy way to make curves on a

Finished parts ready for assembly. Black propeller is smallest North Pacific/Peck size.

You can clearly see the undercambered rib strips. The wheels are made from 1⁄16 sheet

foam with silver paper hubs.

38 MODEL AVIATION

stick-and-tissue model—and it’s much

easier than cutting segments of curves from

1⁄16 balsa sheet and piecing them together.

This is how they did it in the 1930s, but

they did not have such water-based glues or

microwaves then. Technology can make

building faster and better.

Assembly and Painting: After parts are

covered with tissue (use the glue stick on

balsa, then pat the tissue down and trim),

mask off the ailerons, rudder, and elevator

with low-tack masking tape and paper. If

you do not want an accurate color, simply

use the colored tissue. Note that the flying

surfaces are covered on the top only and the

body/fin left side only.

Get a can of Krylon Short Cuts acrylic

aerosol in Espresso (color SCS-035). It will

give your tissue a coffeelike tone—similar

to aged shellac on 1924 aircraft fabric.

Carefully mist a light coat on the exposed

tissue and let it dry before unmasking. Paint

the nose with aluminum acrylic paint from

Wal-Mart.

Attach the rear hook and bearing to the

motorstick (see details on plans), then glue

to the right side of the body as shown on

the plans. Attach the stabilizer, then attach

the fin to the body. Tilt the right side of

the stabilizer up slightly, as seen from the

rear; this will induce a natural right-turn

circle.

Attach the wing to the top of the body;

you may want to pin it at the leading edge

and trailing edge while the Duco dries.

Check to make sure that it is level.

Attach the splayed 1⁄32 plywood landinggear

struts and add the wheels, which can

be glued on. Rotating wheels are not

required; this model is hand launched only.

Add the 1⁄32 plywood rear skid.

Make a rubber motor in approximately a

12-inch loop, tying the ends in a square

knot. Lubricate the motor with Johnson’s

Baby Shampoo and wipe off the excess.

Hang the motor from the shaft and the

rear hook, then wind in a few hand turns,

rotating the propeller clockwise while

holding the nose. Let the propeller breeze

blow in your face—it’s cool!

Check the balance (see plans) with the

motor installed. If necessary, add clay to

the nose in the sheeted section. Correct

balance is essential for Free Flight—or for

any aircraft, piloted or not.

Go to a copy shop and ask for a

discarded box used to ship letter-size copy

paper. Do not use grocery-store boxes; the

lids implode. Put your model in your

storage/transport box, but don’t put any

heavy objects in there with it—a rolling

winder could damage the model.

Flying: It is pointless to test-glide such a

small model. If you fly outdoors (it is

okay to fly in a school gym if it is windy

outdoors), hand wind roughly 200 turns

into the motor and launch the model

straight and level into the wind (10 mph

or less). Do not throw the model!

Your Hawk should fly in a loose right

circle, climbing slightly. Adjust it by

bending the nose bearing to the right for

right thrust and bending the right aileron

down by cracking the tip ribs slightly and

gluing them. This will keep the wing up

(like an aileron) in a turn.

Progress to stretch-winding with the

Peck winder. You will need a flying

buddy to hold the model (upside-down)

by the nose bearing/propeller hub while

you attach the winder and stretch the

motor out approximately twice its length

to the rear.

Put in roughly 100 winder turns while

coming in, then remove the motor from

the winder and attach it to the rear hook.

Take the model from your buddy (give

him/her the winder), and gently launch it.

It should climb out in a loose right circle.

I hope you enjoyed the aviation history

and building this replica of an ill-fated

aircraft. Good luck with your Cooper-

Travers Hawk. Happy landings!

For an issue of the 7/01 Aeroplane

Monthly, send an airmail letter to the

Circulation Department, Aeroplane

Monthly, King’s Reach Tower, Stamford

St., London SE19LS, England.

The cover price is 3.20 pounds, but the

back-issue price plus postage would be in

euros. The easiest way to pay is by major

credit card so there is no trouble with

exchange rates. Include your name as it is

printed on the card, the card’s expiration

date, and the name of the card. That will

expedite your order.

You may order a copy by inquiring by

E-mail to [email protected] or

[email protected]. MA

Dave Linstrum

4016 Maguire Blvd. Apt. 3314

Orlando FL 32803

June 2003 39

Test pilot Lt. Col. Jim Travers flies Cooper-Travers Hawk on approach at Croydon (original London airport) on February 14,

1924, just seconds before fatal crash on first flight. Extremely deep undercambered Gottingen airfoil and 5° positive

incidence on tailplane were likely causes for crash. Ink sketch by author is from photo by Cecil Arthur Rae, who was later a

test pilot for British aircraft manufacturer Boulton Paul.

Edition: Model Aviation - 2003/06

Page Numbers: 35,36,37,38,39,40,41

June 2003 35

■ Dave Linstrum

To launch the Hawk, release propeller tip first,

then let the model fly gently from your hand.

Do not throw!

DEDICATED SCALE enthusiasts often go to great lengths to find obscure full-scale

aircraft to model. They delight in finding something that few fliers have ever heard of,

much less modeled. They spend hours in libraries or on the Internet looking for that

obscure subject that will be the envy of their peers.

I found a complete illustrated dossier on the Cooper-Travers Hawk by accident. I

was in Los Angeles, California (I live in Orlando, Florida), visiting my daughter who

lives in Beverly Hills. I was driving along an urban street and came upon a roadside

newsstand that appeared to have a broad selection of periodicals. I immediately

spotted the July 2001 Aeroplane Monthly—a venerable British publication that

usually has the latest news on aircraft and often has detailed historical articles.

This issue had a gem: a fully illustrated (photos and detailed three-view)

presentation of the 1924 Cooper-Travers Hawk. When I saw the query note by Editor

Michael Oakey, I was hooked! He stated: “It represents a challenging subject for the

aeromodellers among our readership—who will be the first to produce a flying scale

model?”

Thus challenged, I sketched out the model you see here on an SWA barf bag at

35,000 feet shortly after leaving the Los Angeles International Airport. When I got

home, I sent Editor Oakey (himself an aeromodeler) my terse E-mail reply—even

before I glued the first sticks of my FAC (Flying Aces Club) Profile No-Cal Scale

design. I wrote: “A Yank will be first!” He sent his E-mail reply

from London that he was looking forward to hearing more.

I built the model, took flight photos, and mailed them to him as

proof. Indeed, I was first.

In the article “Lesser-Known Aircraft” by distinguished aerohistorian

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume, there is a photo of casual,

intrepid test pilot James L. Travers taken when he was a regular

flier at Hendon Aerodrome (London) in 1912. There is also a

photo of Lt. Col. Jim Travers on approach at Croydon Aerodrome

(London) taken the afternoon of February 14, 1924, captioned:

“ … The aircraft and its designer are seconds from disaster.

The picture shows clearly the extremely deep undercambered

Gottingen wing section, as well as revealing the five-degree angle

of incidence on the unbraced tailplane.”

My ink sketch from that photo shows these two fatal design

flaws. The thick wing was to accommodate two passengers in the

wing root—one on either side of the pilot’s cockpit. Cooper put

the positive incidence in the tailplane, and it gave Travers pause

before he took off, but not enough pause …

A fatal crash on the first test flight was proof enough for me to

eliminate both of those flaws from my model design. I used a

simple undercambered wing rib and set the stabilizer at 0°—a

setup proven on my past No-Cal designs (such as the Dornier

Falke) as stable for Free Flight. I was proven right—and no test

pilot was put at risk.

As Aeroplane stated, “The short life of the one-off Cooper-

Travers Hawk of 1924 has denied it a place in aviation history.

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume investigates why this revolutionary

design ended in a flaming pyre.”

You do not need further history to build this simple replica, but

you can order a back issue of the 7/01 Aeroplane if you want more

details or want to design your own Radio Control version. See the

end of this article for details. I thank that publication and Editor

Oakey for his kind permission to reproduce here the beautifully

drawn Giuseppe Picarella three-view and the preceding quotes.

Giuseppe is a maestro.

CONSTRUCTION

Preparation: Make photocopies (two each—the second set is for

patterns) of the two letter-size plates of building plans. This way

36 MODEL AVIATION

you can avoid cutting up your Model

Aviation. Be sure to hold the magazine

down tight on the copier glass to capture

the image near the binding.

Tape the building plates together along

match line A-B with 3M Scotch Magic

Tape. Tape the plates to your building

board (an 11 x 17-inch scrap of pinstickable

Fome-Cor will do), and cover

with waxed paper to prevent glued balsa

from adhering to the plans.

Materials and Tools: Free Flight stickand-

tissue construction and flying require

special tools and materials. At the least,

you must have an X-Acto (or similar)

model knife with a #11 pointed blade,

bead-head dressmaker pins, a self-healing

cutting board (or a scrap of dark artist’s

matboard), glue (use Duco cement or thickgel

CyA [cyanoacrylate]), a glue stick for

covering with tissue, and needle-nose pliers

for bending the rear hook and propeller

shaft.

Get the preceding items at your local

Wal-Mart. You may need to go to an art

store for the cutting/matboard. Cutting balsa on this is a pleasure.

Do not cut on the plans!

Type: FF FAC Profile No-Cal Scale

Wingspan: 16 inches

Power: 11- to 12-inch loop FAI Tan

II Rubber

Flying weight: 8-10 grams

Construction: Balsa sheet and strip

Covering/finish: Yellow or beige

tissue, Krylon Espresso aerosol

Notice that only one side of the Hawk’s profile fuselage is

covered. This saves weight and keeps the project simple.

Photograph it from the opposite side!

Photos by the author Graphic Design by Carla Kunz

June 2003 37

Few parts make for rapid building, even with the curved tips. All of the parts are shown,

pinned down for drying on the plans. This is a fun project.

Use artist’s matboard or 1⁄16 balsa for templates to form the fin, wingtips, and stabilizer.

Form these parts from wetted 1⁄32 strips.

Most hobby shops do not have the

light balsa and tissue needed to build this

model. An excellent mail-order source is

Peck-Polymers (see the company’s ad in

Model Aviation). To order the complete

catalog for $4, which is a good

investment, call (619) 448-1818. Mail

order is a great resource. Peck is the best

for Free Flight.

You should order 1⁄16 and 1⁄32 balsa

(get small sheets and a dozen 1⁄16 square

sticks), 1⁄32 plywood, a sheet of yellow or

tan Esaki tissue, a 4-inch black square-tip

plastic propeller, a pack of 1⁄32-inchdiameter

shafts, a pack of white nylon

Peanut bearings, a pack of 1-inch black

plastic wheels (unless you want to cut

your own from white carryout tray foam),

a pack of 1⁄8-inch FAI Tan II rubber, a

Peck 5:1 winder for rubber, and the XActo.

Good books to have are Don Ross’s

Rubber Power Flying Models and

Building the Peck ROG by Bill Warner.

Both have many photos and excellent

drawings by Jim Kaman. They will be

treasured in your modeling library. Both

are available from Peck-Polymers.

If you have no stick-and-tissue

experience, order some simple kits: an

AMA Cub (Delta Dart), a Peck ROG, and

perhaps a Sky Bunny. These have

complete, illustrated instructions that will

make you skillful in a hurry. The Hawk is

not a beginner’s model!

Building: I will not tell you how to glue

Part A to Part B; the aforementioned kits

and books will teach you that. The simple

Cooper-Travers Hawk is not an ARF

(Almost Ready-to Fly) with an instruction

book; it is a craftsman’s project requiring

some basic skills.

The sliced wing ribs may be new to

you. Make a rib-slicing pattern from 1⁄32

plywood using the extra plans copy (gluestick

the pattern to the plywood). Cut a

sheet of 1⁄16 balsa to the length of the

center rib, then tape it to the cutting board

at the bottom of the balsa. Slice away

with the X-Acto knife at the top and

discard the scrap, then move the pattern

down 1⁄16 inch. Carefully slice again; you

may need a couple of light strokes.

Cut a full set of ribs. Taper them from

the rear before you glue them in place to

the leading edge and trailing edge. Note

that there is only one center rib, which is

added as you put in the 1-inch dihedral.

Be sure that half of the wing is pinned

down flat as you raise the other tip.

Another unusual method is the wet

lamination of balsa for the round-corner

tips, aileron ends, and fin/rudder. This

requires making forms from artists’

matboard or 1⁄16 balsa; see the photo.

Using the extra “patterns” photocopy

of the plans, glue-stick the tips (one on

each wing and stabilizer) and fin/rudder

to the pattern material. Cut to the inside

line of the double lines of the curved part.

Allow some extra (straight) beyond the

end of the curve; this is for taping the

lamination to the form.

The lamination will be two strips of 1⁄32 x

1⁄16 that appear 1⁄16-inch wide on the plans to

match the 1⁄16 square sticks. Lightly sand the

edges of the patterns and wax them to

prevent glue from sticking the part to the

form.

Cut the strips to length a bit longer than

the form edge, and soak them in hot water

in a saucer. Two at a time, blot excess water

with a paper napkin. Apply a bead of

Titebond or Elmer’s carpenter’s glue to one

strip, then stack the other on top of it,

wiping away any glue that leaks out the

edge. Your lamination is ready to bend

around the form.

Cut two small pieces of 3M Scotch

Magic Tape to hold down the ends. Affix

one end of the strips to the form, pull firmly

and tight to form around the curve, then

affix the other end. Now you are ready for

the fun part.

Put a coffee mug upside down in the

microwave and set the wet part/form atop it.

Microwave for one minute on high, and

presto! You have a permanently curved part

that only needs cutting loose from the form

at the ends. Cut to the line you see at the

end of “straight” for exact length. Discard

the excess with tape. Repeat until you have

all parts; the stabilizer and wingtip/aileron

forms get used twice.

This is the easy way to make curves on a

Finished parts ready for assembly. Black propeller is smallest North Pacific/Peck size.

You can clearly see the undercambered rib strips. The wheels are made from 1⁄16 sheet

foam with silver paper hubs.

38 MODEL AVIATION

stick-and-tissue model—and it’s much

easier than cutting segments of curves from

1⁄16 balsa sheet and piecing them together.

This is how they did it in the 1930s, but

they did not have such water-based glues or

microwaves then. Technology can make

building faster and better.

Assembly and Painting: After parts are

covered with tissue (use the glue stick on

balsa, then pat the tissue down and trim),

mask off the ailerons, rudder, and elevator

with low-tack masking tape and paper. If

you do not want an accurate color, simply

use the colored tissue. Note that the flying

surfaces are covered on the top only and the

body/fin left side only.

Get a can of Krylon Short Cuts acrylic

aerosol in Espresso (color SCS-035). It will

give your tissue a coffeelike tone—similar

to aged shellac on 1924 aircraft fabric.

Carefully mist a light coat on the exposed

tissue and let it dry before unmasking. Paint

the nose with aluminum acrylic paint from

Wal-Mart.

Attach the rear hook and bearing to the

motorstick (see details on plans), then glue

to the right side of the body as shown on

the plans. Attach the stabilizer, then attach

the fin to the body. Tilt the right side of

the stabilizer up slightly, as seen from the

rear; this will induce a natural right-turn

circle.

Attach the wing to the top of the body;

you may want to pin it at the leading edge

and trailing edge while the Duco dries.

Check to make sure that it is level.

Attach the splayed 1⁄32 plywood landinggear

struts and add the wheels, which can

be glued on. Rotating wheels are not

required; this model is hand launched only.

Add the 1⁄32 plywood rear skid.

Make a rubber motor in approximately a

12-inch loop, tying the ends in a square

knot. Lubricate the motor with Johnson’s

Baby Shampoo and wipe off the excess.

Hang the motor from the shaft and the

rear hook, then wind in a few hand turns,

rotating the propeller clockwise while

holding the nose. Let the propeller breeze

blow in your face—it’s cool!

Check the balance (see plans) with the

motor installed. If necessary, add clay to

the nose in the sheeted section. Correct

balance is essential for Free Flight—or for

any aircraft, piloted or not.

Go to a copy shop and ask for a

discarded box used to ship letter-size copy

paper. Do not use grocery-store boxes; the

lids implode. Put your model in your

storage/transport box, but don’t put any

heavy objects in there with it—a rolling

winder could damage the model.

Flying: It is pointless to test-glide such a

small model. If you fly outdoors (it is

okay to fly in a school gym if it is windy

outdoors), hand wind roughly 200 turns

into the motor and launch the model

straight and level into the wind (10 mph

or less). Do not throw the model!

Your Hawk should fly in a loose right

circle, climbing slightly. Adjust it by

bending the nose bearing to the right for

right thrust and bending the right aileron

down by cracking the tip ribs slightly and

gluing them. This will keep the wing up

(like an aileron) in a turn.

Progress to stretch-winding with the

Peck winder. You will need a flying

buddy to hold the model (upside-down)

by the nose bearing/propeller hub while

you attach the winder and stretch the

motor out approximately twice its length

to the rear.

Put in roughly 100 winder turns while

coming in, then remove the motor from

the winder and attach it to the rear hook.

Take the model from your buddy (give

him/her the winder), and gently launch it.

It should climb out in a loose right circle.

I hope you enjoyed the aviation history

and building this replica of an ill-fated

aircraft. Good luck with your Cooper-

Travers Hawk. Happy landings!

For an issue of the 7/01 Aeroplane

Monthly, send an airmail letter to the

Circulation Department, Aeroplane

Monthly, King’s Reach Tower, Stamford

St., London SE19LS, England.

The cover price is 3.20 pounds, but the

back-issue price plus postage would be in

euros. The easiest way to pay is by major

credit card so there is no trouble with

exchange rates. Include your name as it is

printed on the card, the card’s expiration

date, and the name of the card. That will

expedite your order.

You may order a copy by inquiring by

E-mail to [email protected] or

[email protected]. MA

Dave Linstrum

4016 Maguire Blvd. Apt. 3314

Orlando FL 32803

June 2003 39

Test pilot Lt. Col. Jim Travers flies Cooper-Travers Hawk on approach at Croydon (original London airport) on February 14,

1924, just seconds before fatal crash on first flight. Extremely deep undercambered Gottingen airfoil and 5° positive

incidence on tailplane were likely causes for crash. Ink sketch by author is from photo by Cecil Arthur Rae, who was later a

test pilot for British aircraft manufacturer Boulton Paul.

Edition: Model Aviation - 2003/06

Page Numbers: 35,36,37,38,39,40,41

June 2003 35

■ Dave Linstrum

To launch the Hawk, release propeller tip first,

then let the model fly gently from your hand.

Do not throw!

DEDICATED SCALE enthusiasts often go to great lengths to find obscure full-scale

aircraft to model. They delight in finding something that few fliers have ever heard of,

much less modeled. They spend hours in libraries or on the Internet looking for that

obscure subject that will be the envy of their peers.

I found a complete illustrated dossier on the Cooper-Travers Hawk by accident. I

was in Los Angeles, California (I live in Orlando, Florida), visiting my daughter who

lives in Beverly Hills. I was driving along an urban street and came upon a roadside

newsstand that appeared to have a broad selection of periodicals. I immediately

spotted the July 2001 Aeroplane Monthly—a venerable British publication that

usually has the latest news on aircraft and often has detailed historical articles.

This issue had a gem: a fully illustrated (photos and detailed three-view)

presentation of the 1924 Cooper-Travers Hawk. When I saw the query note by Editor

Michael Oakey, I was hooked! He stated: “It represents a challenging subject for the

aeromodellers among our readership—who will be the first to produce a flying scale

model?”

Thus challenged, I sketched out the model you see here on an SWA barf bag at

35,000 feet shortly after leaving the Los Angeles International Airport. When I got

home, I sent Editor Oakey (himself an aeromodeler) my terse E-mail reply—even

before I glued the first sticks of my FAC (Flying Aces Club) Profile No-Cal Scale

design. I wrote: “A Yank will be first!” He sent his E-mail reply

from London that he was looking forward to hearing more.

I built the model, took flight photos, and mailed them to him as

proof. Indeed, I was first.

In the article “Lesser-Known Aircraft” by distinguished aerohistorian

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume, there is a photo of casual,

intrepid test pilot James L. Travers taken when he was a regular

flier at Hendon Aerodrome (London) in 1912. There is also a

photo of Lt. Col. Jim Travers on approach at Croydon Aerodrome

(London) taken the afternoon of February 14, 1924, captioned:

“ … The aircraft and its designer are seconds from disaster.

The picture shows clearly the extremely deep undercambered

Gottingen wing section, as well as revealing the five-degree angle

of incidence on the unbraced tailplane.”

My ink sketch from that photo shows these two fatal design

flaws. The thick wing was to accommodate two passengers in the

wing root—one on either side of the pilot’s cockpit. Cooper put

the positive incidence in the tailplane, and it gave Travers pause

before he took off, but not enough pause …

A fatal crash on the first test flight was proof enough for me to

eliminate both of those flaws from my model design. I used a

simple undercambered wing rib and set the stabilizer at 0°—a

setup proven on my past No-Cal designs (such as the Dornier

Falke) as stable for Free Flight. I was proven right—and no test

pilot was put at risk.

As Aeroplane stated, “The short life of the one-off Cooper-

Travers Hawk of 1924 has denied it a place in aviation history.

Arthur W.J.G. Ord-Hume investigates why this revolutionary

design ended in a flaming pyre.”

You do not need further history to build this simple replica, but

you can order a back issue of the 7/01 Aeroplane if you want more

details or want to design your own Radio Control version. See the

end of this article for details. I thank that publication and Editor

Oakey for his kind permission to reproduce here the beautifully

drawn Giuseppe Picarella three-view and the preceding quotes.

Giuseppe is a maestro.

CONSTRUCTION

Preparation: Make photocopies (two each—the second set is for

patterns) of the two letter-size plates of building plans. This way

36 MODEL AVIATION

you can avoid cutting up your Model

Aviation. Be sure to hold the magazine

down tight on the copier glass to capture

the image near the binding.

Tape the building plates together along

match line A-B with 3M Scotch Magic

Tape. Tape the plates to your building

board (an 11 x 17-inch scrap of pinstickable

Fome-Cor will do), and cover

with waxed paper to prevent glued balsa

from adhering to the plans.

Materials and Tools: Free Flight stickand-

tissue construction and flying require

special tools and materials. At the least,

you must have an X-Acto (or similar)

model knife with a #11 pointed blade,

bead-head dressmaker pins, a self-healing

cutting board (or a scrap of dark artist’s

matboard), glue (use Duco cement or thickgel

CyA [cyanoacrylate]), a glue stick for

covering with tissue, and needle-nose pliers

for bending the rear hook and propeller

shaft.

Get the preceding items at your local

Wal-Mart. You may need to go to an art

store for the cutting/matboard. Cutting balsa on this is a pleasure.

Do not cut on the plans!

Type: FF FAC Profile No-Cal Scale

Wingspan: 16 inches

Power: 11- to 12-inch loop FAI Tan

II Rubber

Flying weight: 8-10 grams

Construction: Balsa sheet and strip

Covering/finish: Yellow or beige

tissue, Krylon Espresso aerosol

Notice that only one side of the Hawk’s profile fuselage is

covered. This saves weight and keeps the project simple.

Photograph it from the opposite side!

Photos by the author Graphic Design by Carla Kunz

June 2003 37

Few parts make for rapid building, even with the curved tips. All of the parts are shown,

pinned down for drying on the plans. This is a fun project.

Use artist’s matboard or 1⁄16 balsa for templates to form the fin, wingtips, and stabilizer.

Form these parts from wetted 1⁄32 strips.

Most hobby shops do not have the

light balsa and tissue needed to build this

model. An excellent mail-order source is

Peck-Polymers (see the company’s ad in

Model Aviation). To order the complete

catalog for $4, which is a good

investment, call (619) 448-1818. Mail

order is a great resource. Peck is the best

for Free Flight.

You should order 1⁄16 and 1⁄32 balsa

(get small sheets and a dozen 1⁄16 square

sticks), 1⁄32 plywood, a sheet of yellow or

tan Esaki tissue, a 4-inch black square-tip

plastic propeller, a pack of 1⁄32-inchdiameter

shafts, a pack of white nylon

Peanut bearings, a pack of 1-inch black

plastic wheels (unless you want to cut

your own from white carryout tray foam),

a pack of 1⁄8-inch FAI Tan II rubber, a

Peck 5:1 winder for rubber, and the XActo.

Good books to have are Don Ross’s

Rubber Power Flying Models and

Building the Peck ROG by Bill Warner.

Both have many photos and excellent

drawings by Jim Kaman. They will be

treasured in your modeling library. Both

are available from Peck-Polymers.

If you have no stick-and-tissue

experience, order some simple kits: an

AMA Cub (Delta Dart), a Peck ROG, and

perhaps a Sky Bunny. These have

complete, illustrated instructions that will

make you skillful in a hurry. The Hawk is

not a beginner’s model!

Building: I will not tell you how to glue

Part A to Part B; the aforementioned kits

and books will teach you that. The simple

Cooper-Travers Hawk is not an ARF

(Almost Ready-to Fly) with an instruction

book; it is a craftsman’s project requiring

some basic skills.

The sliced wing ribs may be new to

you. Make a rib-slicing pattern from 1⁄32

plywood using the extra plans copy (gluestick

the pattern to the plywood). Cut a

sheet of 1⁄16 balsa to the length of the

center rib, then tape it to the cutting board

at the bottom of the balsa. Slice away

with the X-Acto knife at the top and

discard the scrap, then move the pattern

down 1⁄16 inch. Carefully slice again; you

may need a couple of light strokes.

Cut a full set of ribs. Taper them from

the rear before you glue them in place to

the leading edge and trailing edge. Note

that there is only one center rib, which is

added as you put in the 1-inch dihedral.

Be sure that half of the wing is pinned

down flat as you raise the other tip.

Another unusual method is the wet

lamination of balsa for the round-corner

tips, aileron ends, and fin/rudder. This

requires making forms from artists’

matboard or 1⁄16 balsa; see the photo.

Using the extra “patterns” photocopy

of the plans, glue-stick the tips (one on

each wing and stabilizer) and fin/rudder

to the pattern material. Cut to the inside

line of the double lines of the curved part.

Allow some extra (straight) beyond the

end of the curve; this is for taping the

lamination to the form.

The lamination will be two strips of 1⁄32 x

1⁄16 that appear 1⁄16-inch wide on the plans to

match the 1⁄16 square sticks. Lightly sand the

edges of the patterns and wax them to

prevent glue from sticking the part to the

form.

Cut the strips to length a bit longer than

the form edge, and soak them in hot water

in a saucer. Two at a time, blot excess water

with a paper napkin. Apply a bead of

Titebond or Elmer’s carpenter’s glue to one

strip, then stack the other on top of it,

wiping away any glue that leaks out the

edge. Your lamination is ready to bend

around the form.

Cut two small pieces of 3M Scotch

Magic Tape to hold down the ends. Affix

one end of the strips to the form, pull firmly

and tight to form around the curve, then

affix the other end. Now you are ready for

the fun part.

Put a coffee mug upside down in the

microwave and set the wet part/form atop it.

Microwave for one minute on high, and

presto! You have a permanently curved part

that only needs cutting loose from the form

at the ends. Cut to the line you see at the

end of “straight” for exact length. Discard

the excess with tape. Repeat until you have

all parts; the stabilizer and wingtip/aileron

forms get used twice.

This is the easy way to make curves on a

Finished parts ready for assembly. Black propeller is smallest North Pacific/Peck size.

You can clearly see the undercambered rib strips. The wheels are made from 1⁄16 sheet

foam with silver paper hubs.

38 MODEL AVIATION

stick-and-tissue model—and it’s much

easier than cutting segments of curves from

1⁄16 balsa sheet and piecing them together.

This is how they did it in the 1930s, but

they did not have such water-based glues or

microwaves then. Technology can make

building faster and better.

Assembly and Painting: After parts are

covered with tissue (use the glue stick on

balsa, then pat the tissue down and trim),

mask off the ailerons, rudder, and elevator

with low-tack masking tape and paper. If

you do not want an accurate color, simply

use the colored tissue. Note that the flying

surfaces are covered on the top only and the

body/fin left side only.

Get a can of Krylon Short Cuts acrylic

aerosol in Espresso (color SCS-035). It will

give your tissue a coffeelike tone—similar

to aged shellac on 1924 aircraft fabric.

Carefully mist a light coat on the exposed

tissue and let it dry before unmasking. Paint

the nose with aluminum acrylic paint from

Wal-Mart.

Attach the rear hook and bearing to the

motorstick (see details on plans), then glue

to the right side of the body as shown on

the plans. Attach the stabilizer, then attach

the fin to the body. Tilt the right side of

the stabilizer up slightly, as seen from the

rear; this will induce a natural right-turn

circle.

Attach the wing to the top of the body;

you may want to pin it at the leading edge

and trailing edge while the Duco dries.

Check to make sure that it is level.

Attach the splayed 1⁄32 plywood landinggear

struts and add the wheels, which can

be glued on. Rotating wheels are not

required; this model is hand launched only.