106 MODEL AVIATION

TAKING STOCK during the first week of

the new year, I found that I have four kits I’d

like to get built this winter. They are a Marty

Hill Curtiss P-40 Warhawk moldie that spans

48 inches, a Jack Cooper Lockheed P-80

Shooting Star foamie that spans 60 inches, an

Erik Eaton Duster One Design Racer that

spans 60 inches, and a Ray Hayes Olympic III

thermal sailplane, built from traditional balsa

and plywood, that spans 132 inches.

I can’t be certain that I’ll complete all of

them by the time the snow clears here in the

Great Northeast, but right now I’m moving

and grooving on the Marty Hill Warhawk. It’s

a priority, because five guys and I plan to fly

ours in Kansas in May, near the time of the

Midwest Slope Challenge.

That contest will take place May 13-16. The

February 2010 column contains contact

information for this and other slope events that

will be held this year. Be sure to check with

the sponsoring club to confirm event dates.

Yes, five New York Slope Dogs and one

Cape Cod Beach Bum are building Warhawks,

likely to be painted identical as squadron mates, and flown together at

Wilson Lake. It will be grand. Marty has shipped six kits to the group,

and he can mold and send more if other fliers are interested. See the

“Sources” list for his contact information.

The Warhawk comes in what we call a “short kit.” Designed for

experienced builders, a short kit for a molded warbird design provides

the two most difficult parts for a modeler to make: a molded fiberglass

fuselage and hot-wire-cut foam wing cores. A clear molded canopy

might be included, depending on the design.

The short kit will probably include a page or two of building hints

and specifications, such as balance point, decalage angle, and control

throws, but no detailed building instructions. It may come with

drawings that show the layout of radio gear and routing of control

rods, or it might contain, at a minimum, outline drawings of the

vertical and horizontal stabilizers: the parts to be cut from balsa sheet

that the builder supplies.

[[email protected]]

Radio Control Slope Soaring Dave Garwood

Overview of fiberglass-fuselage short kit construction

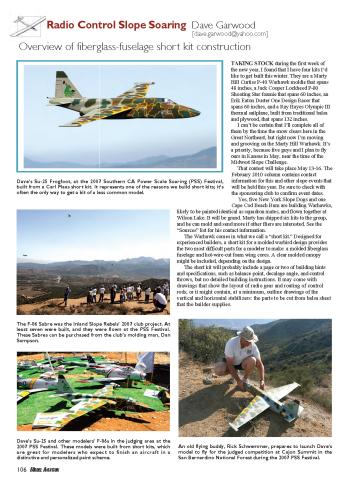

Dave’s Su-25 Frogfoot, at the 2007 Southern CA Power Scale Soaring (PSS) Festival,

built from a Carl Maas short kit. It represents one of the reasons we build short kits; it’s

often the only way to get a kit of a less common model.

An old flying buddy, Rick Schwemmer, prepares to launch Dave’s

model to fly for the judged competition at Cajon Summit in the

San Bernardino National Forest during the 2007 PSS Festival.

Dave’s Su-25 and other modelers’ F-86s in the judging area at the

2007 PSS Festival. These models were built from short kits, which

are great for modelers who expect to finish an aircraft in a

distinctive and personalized paint scheme.

The F-86 Sabre was the Inland Slope Rebels’ 2007 club project. At

least seven were built, and they were flown at the PSS Festival.

These Sabres can be purchased from the club’s molding man, Dan

Sampson.

04sig4.QXD_00MSTRPG.QXD 2/23/10 8:44 AM Page 106

In the Internet age, information for

builders can often be found on a Web site or a

“building thread” on one of the messageposting

pages. For the Warhawk kit, you can

find Marty Hill’s building thread on

RCGroups; the address is in the source list.

A short kit rarely includes wood or

hardware; those decisions and acquisitions are

left up to the builder. What do you get for

your trouble? A tested sailplane design—

perhaps a rare or unusual one that is not

generally available from other sources or

attained by any other method.

If you have enough building experience to

sheet your own foam-core wings, sand and

finish fiberglass parts, design your own radio

installations, and research your own paint

schemes, short kits are for you. I’ve built

eight and have four on the shelf ready to

build. I love them.

Following is an overview of fiberglass-fuselage short kit

construction, but first I’ll tick off the advantages and disadvantages of

composite molded construction compared with wood or EPP foam. (I

discussed these in more detail in the August 2009 Slope Soaring

column.)

Advantages of fiberglass construction:

1) Shape:Molding is probably the best way to get beautiful rounded

and curved shapes.

2) Stiffness: The rigidity of the composite materials allows lighter

airframe construction.

3) Easier construction: Radio installation is easy in a hollow

fuselage. Parts can be glued on with epoxy.

4) Takes paint well: For camouflage markings, paint is the answer—

and fiberglass was made to be painted.

5) Reparability:With molded fiberglass, you can get back to the

original shape, strength, and appearance after a crash.

6) Flies better:Molded sailplanes with sheeted wings penetrate

headwinds better. Molded gliders accelerate quicker, have higher top

speeds, and fly better in off-direction lift. The real deal, go-fast

sailplanes are molded. Fly a fiberglass Slope Soarer after flying a

foamie, and you’re in for a pleasant surprise.

Disadvantages of fiberglass construction:

1) Higher cost: Composite model parts might be more expensive

than an equivalent-size wood or foam construction design. Building

time will likely be longer with composites, which, in effect, adds to the

price.

2) Learning curve: The techniques used to build and finish molded

fiberglass might be new to some builders, depending on their previous

experience. But hey, foamie construction was new at one time too.

3) Fear of breaking the model: This is possibly the largest fear that

keeps pilots from trying fiberglass. Yes, these aircraft can be broken,

but they can be repaired to 100% in strength and appearance—and

that’s not always possible with foam construction.

Are you ready to review the steps to build a fiberglass short kit? Let’s

get started.

1) Open the box and inventory the parts. It’s a thrill to pull the

pieces out of a new kit box and examine them. It’s at this point that I

begin to imagine the sailplane built, painted, and flying.

Check the molded fuselage, examine the wing cores, and review the

information that comes with the kit. Perhaps begin making a list of tools

and materials you’ll need for construction.

If that info is not in the kit or part of your previous building

experience, check for an online building log, search the MA or RC

Soaring Digest online archives for a building how-to article, or get

advice from more-experienced builders.

2) Sheet the wing. A foam-core, wood-sheeted wing offers many

benefits for slope sailplanes. It produces stiff and light wings, which

April 2010 107

Typical for a short kit, the Su-25 included a molded-fiberglass

fuselage, hot-wire-cut foam cores for sheeted wings, and a molded

clear canopy. Also included were drawings for tail parts. If there is

sufficient reader interest, Dave will write more about short kit

building skills.

Short kit builders at the 2007 PSS Festival (L-R): Brian Koester (F-86 “Sky Blazers”), Ian

Gittins (F-86 “ANG”), Russ Thompson (Focke-Wulf P-1), Dave Garwood (“Su-25”), and

Jeff Fukushima (F-86 “Sky Blazers”).

can be repaired with a reasonable amount of effort.

To sheet wings, prepare “skins” by joining 1/16 balsa sheeting or

similar wood veneer material, such as obechi or 1/64 plywood. Sand the

skins, sand the cores, and cut pieces slightly larger than the cores—

roughly 1/4 inch all around works well.

Adhesives that work for attaching the skins include double-stick

tape, brush-on contact cement, spray-on contact cement, and epoxy.

After you have sheeted the cores, trim them flush and sand them

square. Add the recommended LE sticks (often hard balsa or

basswood) and the balsa sub-TE sticks, and shape to the specified

airfoil shape.

3) Cut the balsa parts using balsa stock that you provide. Some of

the components include wingtip blocks, vertical and horizontal

stabilizers, and elevators. The short kit instructions often include

cutting templates and specify the thickness of the balsa stock. If they

don’t, check with the designer or the research methods I mentioned for

getting how-to info.

4) Construct the wing and fit and shape the tips. Fit the aileron

torque-rod assemblies. Shape the ailerons, and install them using the

hinge method you like best. Join the wing halves, remembering to set

the dihedral to specification. Add layers of fiberglass cloth and epoxy

resin, to strengthen the wing center joint.

5) Prepare the fuselage.Wet-sand the fuselage to remove the moldrelease

agent and break the glaze on the fiberglass, to allow it to take

paint well. Apply primer paint, fill holes with common auto-body

repair materials (Bondo is a favorite brand), and wet-sand again.

Repeat as necessary to get a smooth finish that is ready to take the final

color coat.

6) Mount the wing and tail parts. You may be deciding whether to

build a removable wing for easier storage and transportation or a fixed

wing for a stronger airframe. One thing to keep in mind is that the joint

between the wing and fuselage can be faired with Bondo more

smoothly with a one-piece airframe.

7) Install radio components and control linkages.Most slope

warbirds with spans as large as 50 inches are controlled by two

04sig4.QXD_00MSTRPG.QXD 2/23/10 8:45 AM Page 107

channels—aileron and elevator—so the radio

installation consists of five components: two

servos, receiver, battery pack, and switch.

During installation, try to get the heavier

components as far forward as possible, to

reduce the nose weight that you must add to

balance the model.

8) Cover, paint, and apply markings.

Apply your selected covering material.

Solartex iron-on fabric is a favorite for slope

warbirds because of its toughness. It might be

too heavy for a longer-wing slope sailplane

such as a racer.

Another reason why I like Solartex is that

it takes paint well. And the fiberglass fuselage

and covered wing and tail parts can be

matched in color, with airbrush or rattle-can

painting.

Apply markings—either national insignia

or canopy markings for a warbird or slope jet

or bold and distinctive markings for a racer.

Take a moment to admire your work; this is

quite an accomplishment. No one else has a

model that looks exactly like yours.

9) Check balance and correct-direction

control throws before test-flying. A noseheavy

aircraft maneuvers sluggishly and can

be corrected on the second flight, while a tailheavy

model might be so uncontrollable that

there is no second flight.

Triple-check control-surface movements

for correct and free operation. On a new

airframe, I have another pilot triple-check the

control-surface movements; that might

preclude a preventable crash.

Using the methods I’ve summarized, I can

get an airframe ready to fly in 26-30 shop

hours. I can paint and detail the sailplane in

another six to 12 shop hours.

I’ve built eight models this way, and I

have four short kits in stock for future

building. If there is enough reader interest,

I’ll be happy to write in more detail about the

construction methods: wing sheeting,

fiberglass finishing, and airbrush painting. MA

Sources:

RCGroups

www.rcgroups.com

Marty Hill

[email protected]

Marty Hill P-40 short kit description

www.rcgroups.com/forums/showthread.php?

t=992094

Marty Hill P-40 build thread:

www.rcgroups.com/forums/showthread.php?

t=738935

Dan Sampson (molds Inland Slope Rebels

club-project short kits):

[email protected]

MA online archives:

http://modelaircraft.org/mag

RC Soaring Digest online archives:

www.rcsoaringdigest.com

www.rcsoaringdigest.com/pdfs

Edition: Model Aviation - 2010/04

Page Numbers: 106,107,108

Edition: Model Aviation - 2010/04

Page Numbers: 106,107,108

106 MODEL AVIATION

TAKING STOCK during the first week of

the new year, I found that I have four kits I’d

like to get built this winter. They are a Marty

Hill Curtiss P-40 Warhawk moldie that spans

48 inches, a Jack Cooper Lockheed P-80

Shooting Star foamie that spans 60 inches, an

Erik Eaton Duster One Design Racer that

spans 60 inches, and a Ray Hayes Olympic III

thermal sailplane, built from traditional balsa

and plywood, that spans 132 inches.

I can’t be certain that I’ll complete all of

them by the time the snow clears here in the

Great Northeast, but right now I’m moving

and grooving on the Marty Hill Warhawk. It’s

a priority, because five guys and I plan to fly

ours in Kansas in May, near the time of the

Midwest Slope Challenge.

That contest will take place May 13-16. The

February 2010 column contains contact

information for this and other slope events that

will be held this year. Be sure to check with

the sponsoring club to confirm event dates.

Yes, five New York Slope Dogs and one

Cape Cod Beach Bum are building Warhawks,

likely to be painted identical as squadron mates, and flown together at

Wilson Lake. It will be grand. Marty has shipped six kits to the group,

and he can mold and send more if other fliers are interested. See the

“Sources” list for his contact information.

The Warhawk comes in what we call a “short kit.” Designed for

experienced builders, a short kit for a molded warbird design provides

the two most difficult parts for a modeler to make: a molded fiberglass

fuselage and hot-wire-cut foam wing cores. A clear molded canopy

might be included, depending on the design.

The short kit will probably include a page or two of building hints

and specifications, such as balance point, decalage angle, and control

throws, but no detailed building instructions. It may come with

drawings that show the layout of radio gear and routing of control

rods, or it might contain, at a minimum, outline drawings of the

vertical and horizontal stabilizers: the parts to be cut from balsa sheet

that the builder supplies.

[[email protected]]

Radio Control Slope Soaring Dave Garwood

Overview of fiberglass-fuselage short kit construction

Dave’s Su-25 Frogfoot, at the 2007 Southern CA Power Scale Soaring (PSS) Festival,

built from a Carl Maas short kit. It represents one of the reasons we build short kits; it’s

often the only way to get a kit of a less common model.

An old flying buddy, Rick Schwemmer, prepares to launch Dave’s

model to fly for the judged competition at Cajon Summit in the

San Bernardino National Forest during the 2007 PSS Festival.

Dave’s Su-25 and other modelers’ F-86s in the judging area at the

2007 PSS Festival. These models were built from short kits, which

are great for modelers who expect to finish an aircraft in a

distinctive and personalized paint scheme.

The F-86 Sabre was the Inland Slope Rebels’ 2007 club project. At

least seven were built, and they were flown at the PSS Festival.

These Sabres can be purchased from the club’s molding man, Dan

Sampson.

04sig4.QXD_00MSTRPG.QXD 2/23/10 8:44 AM Page 106

In the Internet age, information for

builders can often be found on a Web site or a

“building thread” on one of the messageposting

pages. For the Warhawk kit, you can

find Marty Hill’s building thread on

RCGroups; the address is in the source list.

A short kit rarely includes wood or

hardware; those decisions and acquisitions are

left up to the builder. What do you get for

your trouble? A tested sailplane design—

perhaps a rare or unusual one that is not

generally available from other sources or

attained by any other method.

If you have enough building experience to

sheet your own foam-core wings, sand and

finish fiberglass parts, design your own radio

installations, and research your own paint

schemes, short kits are for you. I’ve built

eight and have four on the shelf ready to

build. I love them.

Following is an overview of fiberglass-fuselage short kit

construction, but first I’ll tick off the advantages and disadvantages of

composite molded construction compared with wood or EPP foam. (I

discussed these in more detail in the August 2009 Slope Soaring

column.)

Advantages of fiberglass construction:

1) Shape:Molding is probably the best way to get beautiful rounded

and curved shapes.

2) Stiffness: The rigidity of the composite materials allows lighter

airframe construction.

3) Easier construction: Radio installation is easy in a hollow

fuselage. Parts can be glued on with epoxy.

4) Takes paint well: For camouflage markings, paint is the answer—

and fiberglass was made to be painted.

5) Reparability:With molded fiberglass, you can get back to the

original shape, strength, and appearance after a crash.

6) Flies better:Molded sailplanes with sheeted wings penetrate

headwinds better. Molded gliders accelerate quicker, have higher top

speeds, and fly better in off-direction lift. The real deal, go-fast

sailplanes are molded. Fly a fiberglass Slope Soarer after flying a

foamie, and you’re in for a pleasant surprise.

Disadvantages of fiberglass construction:

1) Higher cost: Composite model parts might be more expensive

than an equivalent-size wood or foam construction design. Building

time will likely be longer with composites, which, in effect, adds to the

price.

2) Learning curve: The techniques used to build and finish molded

fiberglass might be new to some builders, depending on their previous

experience. But hey, foamie construction was new at one time too.

3) Fear of breaking the model: This is possibly the largest fear that

keeps pilots from trying fiberglass. Yes, these aircraft can be broken,

but they can be repaired to 100% in strength and appearance—and

that’s not always possible with foam construction.

Are you ready to review the steps to build a fiberglass short kit? Let’s

get started.

1) Open the box and inventory the parts. It’s a thrill to pull the

pieces out of a new kit box and examine them. It’s at this point that I

begin to imagine the sailplane built, painted, and flying.

Check the molded fuselage, examine the wing cores, and review the

information that comes with the kit. Perhaps begin making a list of tools

and materials you’ll need for construction.

If that info is not in the kit or part of your previous building

experience, check for an online building log, search the MA or RC

Soaring Digest online archives for a building how-to article, or get

advice from more-experienced builders.

2) Sheet the wing. A foam-core, wood-sheeted wing offers many

benefits for slope sailplanes. It produces stiff and light wings, which

April 2010 107

Typical for a short kit, the Su-25 included a molded-fiberglass

fuselage, hot-wire-cut foam cores for sheeted wings, and a molded

clear canopy. Also included were drawings for tail parts. If there is

sufficient reader interest, Dave will write more about short kit

building skills.

Short kit builders at the 2007 PSS Festival (L-R): Brian Koester (F-86 “Sky Blazers”), Ian

Gittins (F-86 “ANG”), Russ Thompson (Focke-Wulf P-1), Dave Garwood (“Su-25”), and

Jeff Fukushima (F-86 “Sky Blazers”).

can be repaired with a reasonable amount of effort.

To sheet wings, prepare “skins” by joining 1/16 balsa sheeting or

similar wood veneer material, such as obechi or 1/64 plywood. Sand the

skins, sand the cores, and cut pieces slightly larger than the cores—

roughly 1/4 inch all around works well.

Adhesives that work for attaching the skins include double-stick

tape, brush-on contact cement, spray-on contact cement, and epoxy.

After you have sheeted the cores, trim them flush and sand them

square. Add the recommended LE sticks (often hard balsa or

basswood) and the balsa sub-TE sticks, and shape to the specified

airfoil shape.

3) Cut the balsa parts using balsa stock that you provide. Some of

the components include wingtip blocks, vertical and horizontal

stabilizers, and elevators. The short kit instructions often include

cutting templates and specify the thickness of the balsa stock. If they

don’t, check with the designer or the research methods I mentioned for

getting how-to info.

4) Construct the wing and fit and shape the tips. Fit the aileron

torque-rod assemblies. Shape the ailerons, and install them using the

hinge method you like best. Join the wing halves, remembering to set

the dihedral to specification. Add layers of fiberglass cloth and epoxy

resin, to strengthen the wing center joint.

5) Prepare the fuselage.Wet-sand the fuselage to remove the moldrelease

agent and break the glaze on the fiberglass, to allow it to take

paint well. Apply primer paint, fill holes with common auto-body

repair materials (Bondo is a favorite brand), and wet-sand again.

Repeat as necessary to get a smooth finish that is ready to take the final

color coat.

6) Mount the wing and tail parts. You may be deciding whether to

build a removable wing for easier storage and transportation or a fixed

wing for a stronger airframe. One thing to keep in mind is that the joint

between the wing and fuselage can be faired with Bondo more

smoothly with a one-piece airframe.

7) Install radio components and control linkages.Most slope

warbirds with spans as large as 50 inches are controlled by two

04sig4.QXD_00MSTRPG.QXD 2/23/10 8:45 AM Page 107

channels—aileron and elevator—so the radio

installation consists of five components: two

servos, receiver, battery pack, and switch.

During installation, try to get the heavier

components as far forward as possible, to

reduce the nose weight that you must add to

balance the model.

8) Cover, paint, and apply markings.

Apply your selected covering material.

Solartex iron-on fabric is a favorite for slope

warbirds because of its toughness. It might be

too heavy for a longer-wing slope sailplane

such as a racer.

Another reason why I like Solartex is that

it takes paint well. And the fiberglass fuselage

and covered wing and tail parts can be

matched in color, with airbrush or rattle-can

painting.

Apply markings—either national insignia

or canopy markings for a warbird or slope jet

or bold and distinctive markings for a racer.

Take a moment to admire your work; this is

quite an accomplishment. No one else has a

model that looks exactly like yours.

9) Check balance and correct-direction

control throws before test-flying. A noseheavy

aircraft maneuvers sluggishly and can

be corrected on the second flight, while a tailheavy

model might be so uncontrollable that

there is no second flight.

Triple-check control-surface movements

for correct and free operation. On a new

airframe, I have another pilot triple-check the

control-surface movements; that might

preclude a preventable crash.

Using the methods I’ve summarized, I can

get an airframe ready to fly in 26-30 shop

hours. I can paint and detail the sailplane in

another six to 12 shop hours.

I’ve built eight models this way, and I

have four short kits in stock for future

building. If there is enough reader interest,

I’ll be happy to write in more detail about the

construction methods: wing sheeting,

fiberglass finishing, and airbrush painting. MA

Sources:

RCGroups

www.rcgroups.com

Marty Hill

[email protected]

Marty Hill P-40 short kit description

www.rcgroups.com/forums/showthread.php?

t=992094

Marty Hill P-40 build thread:

www.rcgroups.com/forums/showthread.php?

t=738935

Dan Sampson (molds Inland Slope Rebels

club-project short kits):

[email protected]

MA online archives:

http://modelaircraft.org/mag

RC Soaring Digest online archives:

www.rcsoaringdigest.com

www.rcsoaringdigest.com/pdfs

Edition: Model Aviation - 2010/04

Page Numbers: 106,107,108

106 MODEL AVIATION

TAKING STOCK during the first week of

the new year, I found that I have four kits I’d

like to get built this winter. They are a Marty

Hill Curtiss P-40 Warhawk moldie that spans

48 inches, a Jack Cooper Lockheed P-80

Shooting Star foamie that spans 60 inches, an

Erik Eaton Duster One Design Racer that

spans 60 inches, and a Ray Hayes Olympic III

thermal sailplane, built from traditional balsa

and plywood, that spans 132 inches.

I can’t be certain that I’ll complete all of

them by the time the snow clears here in the

Great Northeast, but right now I’m moving

and grooving on the Marty Hill Warhawk. It’s

a priority, because five guys and I plan to fly

ours in Kansas in May, near the time of the

Midwest Slope Challenge.

That contest will take place May 13-16. The

February 2010 column contains contact

information for this and other slope events that

will be held this year. Be sure to check with

the sponsoring club to confirm event dates.

Yes, five New York Slope Dogs and one

Cape Cod Beach Bum are building Warhawks,

likely to be painted identical as squadron mates, and flown together at

Wilson Lake. It will be grand. Marty has shipped six kits to the group,

and he can mold and send more if other fliers are interested. See the

“Sources” list for his contact information.

The Warhawk comes in what we call a “short kit.” Designed for

experienced builders, a short kit for a molded warbird design provides

the two most difficult parts for a modeler to make: a molded fiberglass

fuselage and hot-wire-cut foam wing cores. A clear molded canopy

might be included, depending on the design.

The short kit will probably include a page or two of building hints

and specifications, such as balance point, decalage angle, and control

throws, but no detailed building instructions. It may come with

drawings that show the layout of radio gear and routing of control

rods, or it might contain, at a minimum, outline drawings of the

vertical and horizontal stabilizers: the parts to be cut from balsa sheet

that the builder supplies.

[[email protected]]

Radio Control Slope Soaring Dave Garwood

Overview of fiberglass-fuselage short kit construction

Dave’s Su-25 Frogfoot, at the 2007 Southern CA Power Scale Soaring (PSS) Festival,

built from a Carl Maas short kit. It represents one of the reasons we build short kits; it’s

often the only way to get a kit of a less common model.

An old flying buddy, Rick Schwemmer, prepares to launch Dave’s

model to fly for the judged competition at Cajon Summit in the

San Bernardino National Forest during the 2007 PSS Festival.

Dave’s Su-25 and other modelers’ F-86s in the judging area at the

2007 PSS Festival. These models were built from short kits, which

are great for modelers who expect to finish an aircraft in a

distinctive and personalized paint scheme.

The F-86 Sabre was the Inland Slope Rebels’ 2007 club project. At

least seven were built, and they were flown at the PSS Festival.

These Sabres can be purchased from the club’s molding man, Dan

Sampson.

04sig4.QXD_00MSTRPG.QXD 2/23/10 8:44 AM Page 106

In the Internet age, information for

builders can often be found on a Web site or a

“building thread” on one of the messageposting

pages. For the Warhawk kit, you can

find Marty Hill’s building thread on

RCGroups; the address is in the source list.

A short kit rarely includes wood or

hardware; those decisions and acquisitions are

left up to the builder. What do you get for

your trouble? A tested sailplane design—

perhaps a rare or unusual one that is not

generally available from other sources or

attained by any other method.

If you have enough building experience to

sheet your own foam-core wings, sand and

finish fiberglass parts, design your own radio

installations, and research your own paint

schemes, short kits are for you. I’ve built

eight and have four on the shelf ready to

build. I love them.

Following is an overview of fiberglass-fuselage short kit

construction, but first I’ll tick off the advantages and disadvantages of

composite molded construction compared with wood or EPP foam. (I

discussed these in more detail in the August 2009 Slope Soaring

column.)

Advantages of fiberglass construction:

1) Shape:Molding is probably the best way to get beautiful rounded

and curved shapes.

2) Stiffness: The rigidity of the composite materials allows lighter

airframe construction.

3) Easier construction: Radio installation is easy in a hollow

fuselage. Parts can be glued on with epoxy.

4) Takes paint well: For camouflage markings, paint is the answer—

and fiberglass was made to be painted.

5) Reparability:With molded fiberglass, you can get back to the

original shape, strength, and appearance after a crash.

6) Flies better:Molded sailplanes with sheeted wings penetrate

headwinds better. Molded gliders accelerate quicker, have higher top

speeds, and fly better in off-direction lift. The real deal, go-fast

sailplanes are molded. Fly a fiberglass Slope Soarer after flying a

foamie, and you’re in for a pleasant surprise.

Disadvantages of fiberglass construction:

1) Higher cost: Composite model parts might be more expensive

than an equivalent-size wood or foam construction design. Building

time will likely be longer with composites, which, in effect, adds to the

price.

2) Learning curve: The techniques used to build and finish molded

fiberglass might be new to some builders, depending on their previous

experience. But hey, foamie construction was new at one time too.

3) Fear of breaking the model: This is possibly the largest fear that

keeps pilots from trying fiberglass. Yes, these aircraft can be broken,

but they can be repaired to 100% in strength and appearance—and

that’s not always possible with foam construction.

Are you ready to review the steps to build a fiberglass short kit? Let’s

get started.

1) Open the box and inventory the parts. It’s a thrill to pull the

pieces out of a new kit box and examine them. It’s at this point that I

begin to imagine the sailplane built, painted, and flying.

Check the molded fuselage, examine the wing cores, and review the

information that comes with the kit. Perhaps begin making a list of tools

and materials you’ll need for construction.

If that info is not in the kit or part of your previous building

experience, check for an online building log, search the MA or RC

Soaring Digest online archives for a building how-to article, or get

advice from more-experienced builders.

2) Sheet the wing. A foam-core, wood-sheeted wing offers many

benefits for slope sailplanes. It produces stiff and light wings, which

April 2010 107

Typical for a short kit, the Su-25 included a molded-fiberglass

fuselage, hot-wire-cut foam cores for sheeted wings, and a molded

clear canopy. Also included were drawings for tail parts. If there is

sufficient reader interest, Dave will write more about short kit

building skills.

Short kit builders at the 2007 PSS Festival (L-R): Brian Koester (F-86 “Sky Blazers”), Ian

Gittins (F-86 “ANG”), Russ Thompson (Focke-Wulf P-1), Dave Garwood (“Su-25”), and

Jeff Fukushima (F-86 “Sky Blazers”).

can be repaired with a reasonable amount of effort.

To sheet wings, prepare “skins” by joining 1/16 balsa sheeting or

similar wood veneer material, such as obechi or 1/64 plywood. Sand the

skins, sand the cores, and cut pieces slightly larger than the cores—

roughly 1/4 inch all around works well.

Adhesives that work for attaching the skins include double-stick

tape, brush-on contact cement, spray-on contact cement, and epoxy.

After you have sheeted the cores, trim them flush and sand them

square. Add the recommended LE sticks (often hard balsa or

basswood) and the balsa sub-TE sticks, and shape to the specified

airfoil shape.

3) Cut the balsa parts using balsa stock that you provide. Some of

the components include wingtip blocks, vertical and horizontal

stabilizers, and elevators. The short kit instructions often include

cutting templates and specify the thickness of the balsa stock. If they

don’t, check with the designer or the research methods I mentioned for

getting how-to info.

4) Construct the wing and fit and shape the tips. Fit the aileron

torque-rod assemblies. Shape the ailerons, and install them using the

hinge method you like best. Join the wing halves, remembering to set

the dihedral to specification. Add layers of fiberglass cloth and epoxy

resin, to strengthen the wing center joint.

5) Prepare the fuselage.Wet-sand the fuselage to remove the moldrelease

agent and break the glaze on the fiberglass, to allow it to take

paint well. Apply primer paint, fill holes with common auto-body

repair materials (Bondo is a favorite brand), and wet-sand again.

Repeat as necessary to get a smooth finish that is ready to take the final

color coat.

6) Mount the wing and tail parts. You may be deciding whether to

build a removable wing for easier storage and transportation or a fixed

wing for a stronger airframe. One thing to keep in mind is that the joint

between the wing and fuselage can be faired with Bondo more

smoothly with a one-piece airframe.

7) Install radio components and control linkages.Most slope

warbirds with spans as large as 50 inches are controlled by two

04sig4.QXD_00MSTRPG.QXD 2/23/10 8:45 AM Page 107

channels—aileron and elevator—so the radio

installation consists of five components: two

servos, receiver, battery pack, and switch.

During installation, try to get the heavier

components as far forward as possible, to

reduce the nose weight that you must add to

balance the model.

8) Cover, paint, and apply markings.

Apply your selected covering material.

Solartex iron-on fabric is a favorite for slope

warbirds because of its toughness. It might be

too heavy for a longer-wing slope sailplane

such as a racer.

Another reason why I like Solartex is that

it takes paint well. And the fiberglass fuselage

and covered wing and tail parts can be

matched in color, with airbrush or rattle-can

painting.

Apply markings—either national insignia

or canopy markings for a warbird or slope jet

or bold and distinctive markings for a racer.

Take a moment to admire your work; this is

quite an accomplishment. No one else has a

model that looks exactly like yours.

9) Check balance and correct-direction

control throws before test-flying. A noseheavy

aircraft maneuvers sluggishly and can

be corrected on the second flight, while a tailheavy

model might be so uncontrollable that

there is no second flight.

Triple-check control-surface movements

for correct and free operation. On a new

airframe, I have another pilot triple-check the

control-surface movements; that might

preclude a preventable crash.

Using the methods I’ve summarized, I can

get an airframe ready to fly in 26-30 shop

hours. I can paint and detail the sailplane in

another six to 12 shop hours.

I’ve built eight models this way, and I

have four short kits in stock for future

building. If there is enough reader interest,

I’ll be happy to write in more detail about the

construction methods: wing sheeting,

fiberglass finishing, and airbrush painting. MA

Sources:

RCGroups

www.rcgroups.com

Marty Hill

[email protected]

Marty Hill P-40 short kit description

www.rcgroups.com/forums/showthread.php?

t=992094

Marty Hill P-40 build thread:

www.rcgroups.com/forums/showthread.php?

t=738935

Dan Sampson (molds Inland Slope Rebels

club-project short kits):

[email protected]

MA online archives:

http://modelaircraft.org/mag

RC Soaring Digest online archives:

www.rcsoaringdigest.com

www.rcsoaringdigest.com/pdfs